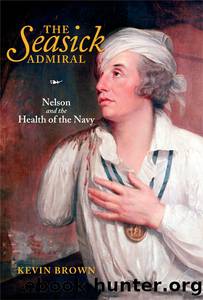

The Seasick Admiral: Nelson and the Health of the Navy by Kevin Brown

Author:Kevin Brown [Brown, Kevin]

Language: eng

Format: epub

Tags: History, Military, Naval, Modern, 19th Century, Napoleonic Wars

ISBN: 9781848324183

Google: B2TNDwAAQBAJ

Amazon: B017XNH6UI

Goodreads: 27868835

Publisher: Pen and Sword

Published: 2015-10-30T00:00:00+00:00

7

Keeping the Seamen Healthy

It was Nelsonâs firm belief that âthe great thing in all military service is health and it is easier for an officer to keep men healthy than for a physician to cure themâ.1 John Snipe, Physician to the Mediterranean Fleet, urged the vital importance of paying close attention to shipboard hygiene, ensuring that seamen were adequately clothed, that the ships were well-ventilated, clean and dry, that sick berths were fit for purpose and that there should be âas nourishing a diet as situation and local circumstances will permit, composed of fresh meat and succulent vegetablesâ. This was possible only if naval officers at all levels collaborated with the shipsâ surgeons since ânearly the whole of this is hinged on the improved mode of discipline which at this moment enables the British fleet to ride triumphant on the seas, and bid defiance to the hostile bands of our combined foesâ.2 Nelson was adamant that in order to wage a successful naval war âthe health of our seamen is invaluable, and to purchase that no expense ought to be sparedâ.3

If the crew were to be kept healthy, it was essential that the vessel on which they sailed should be a clean ship. Yet warships were designed to be formidable in battle or in maintaining a blockade rather than for the health of the men on board. Disease was perhaps a greater danger than death in battle and it was not easy to prevent infection from getting hold and spreading. The battleships were overcrowded. A third rate ship of 1800 tons would have about 600 men. A 100-gun, three-decker such as Victory carried some 900 men. Much healthier were the single-decked fifth or sixth rate frigates where the air could circulate more freely. Yet, the close proximity of the men to each other where 14 inches was officially allowed for each man to sling a hammock, meant that infection could spread quickly.4

Ventilation was a particular problem that was exacerbated in stormy weather and high seas when the ports and hatches had to be closed. In the totally unventilated well of the ship with its ballast it was necessary, as in contemporary coalmines, to lower a lighted candle into the well to test for noxious gases and firedamp before a carpenter would descend to inspect the pumps. If a candle was unavailable, the quality of the air in the hold would be tested by seeing how long it took for a silver spoon to tarnish. Gilbert Blane commented that âit will appear hardly credible to succeeding generations that the air of the well of a ship could become so contaminated as in innumerable instances to produce instantaneous and irremediable suffocationâ.5

At that time it was believed that infection was caused by miasma or foul-smelling bad air emanating from decomposed organic matter. It was held that good ventilation and circulation of air was essential to prevent miasmatic disease, but actually proved beneficial in an unintended way by reducing the risk of airborne bacterial infection.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

The Radium Girls by Kate Moore(12028)

100 Deadly Skills by Clint Emerson(4926)

Rise and Kill First by Ronen Bergman(4789)

The Templars by Dan Jones(4689)

The Doomsday Machine by Daniel Ellsberg(4490)

The Rape of Nanking by Iris Chang(4213)

Killing England by Bill O'Reilly(4004)

Stalin by Stephen Kotkin(3968)

Hitler in Los Angeles by Steven J. Ross(3946)

12 Strong by Doug Stanton(3550)

Hitler's Monsters by Eric Kurlander(3343)

Blood and Sand by Alex Von Tunzelmann(3205)

The Code Book by Simon Singh(3189)

Darkest Hour by Anthony McCarten(3133)

The Art of War Visualized by Jessica Hagy(3008)

Hitler's Flying Saucers: A Guide to German Flying Discs of the Second World War by Stevens Henry(2754)

Babylon's Ark by Lawrence Anthony(2679)

The Second World Wars by Victor Davis Hanson(2526)

Tobruk by Peter Fitzsimons(2518)